“Tokyo Drifter” 4K digital restoration: Authentically restoring the film’s color

From June 22, 2024, “Tokyo Drifter” (1996; Nikkatsu Corporation; directed by Seijun Suzuki) will be screened at the Il Cinema Ritrovato film festival in Bologna, Italy. A major feature of the work is its vividly colored sets and costumes, which are used to express the film’s unique worldview. In the digital restoration process, we aimed to “authentically restore” the film by analyzing the characteristics of color film at the time of its original release. To commemorate this world premier screening, we are pleased to share the restoration process.

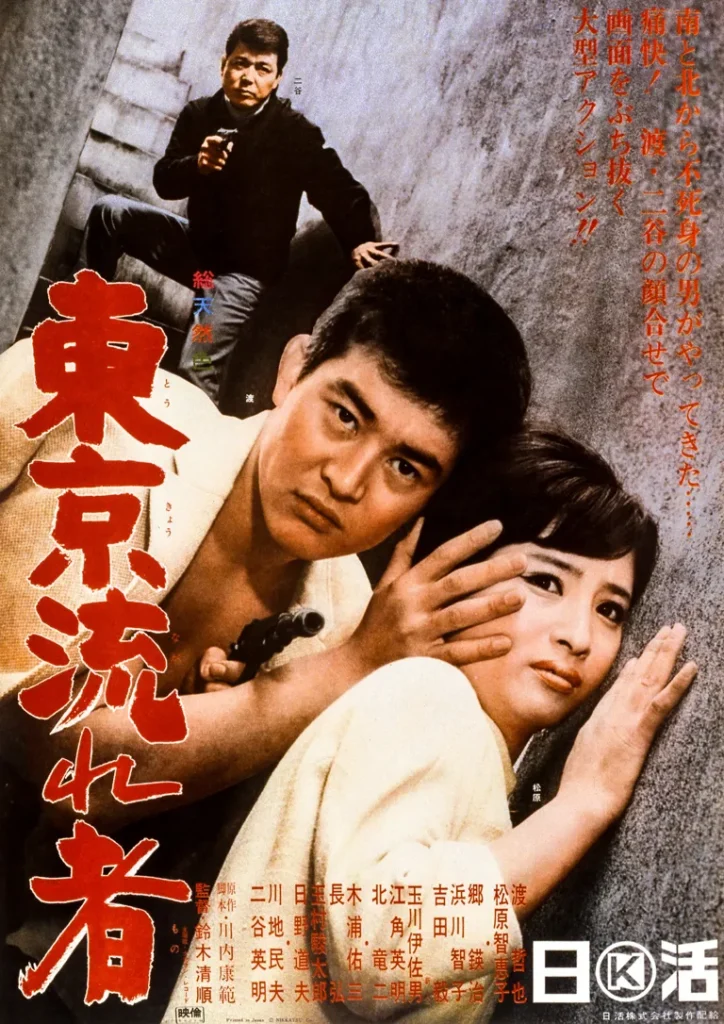

About “Tokyo Drifter”

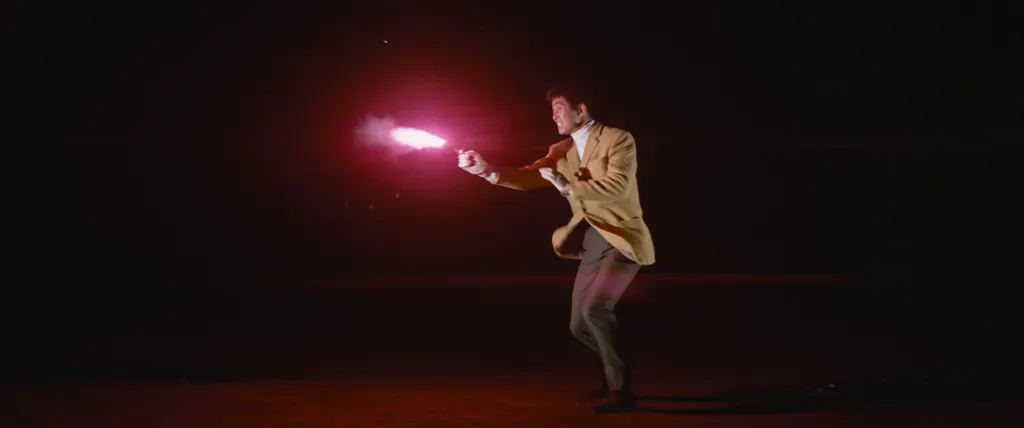

“Don't piss me off!” Testsuya Hondo (Tetsuya Watari), otherwise known as “Tetsu the Phoenix,” is surrounded by some thugs. Tetsu is a member of the Kurata gang which had recently turned straight by starting a real estate business — but the rivaling Otsuka gang does not like this at all. Despite Tetsu’s effort to remain passive, Otsuka’s gangs will not leave him alone.

Authentically restoring a color work

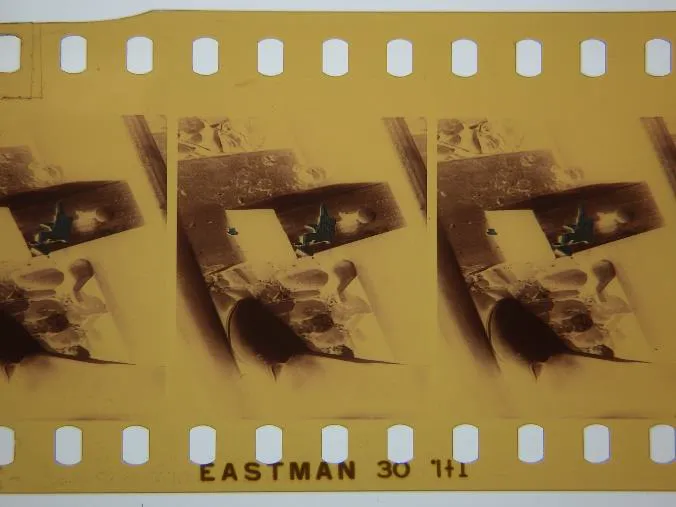

“Tokyo Drifter” Original 35mm camera negatives

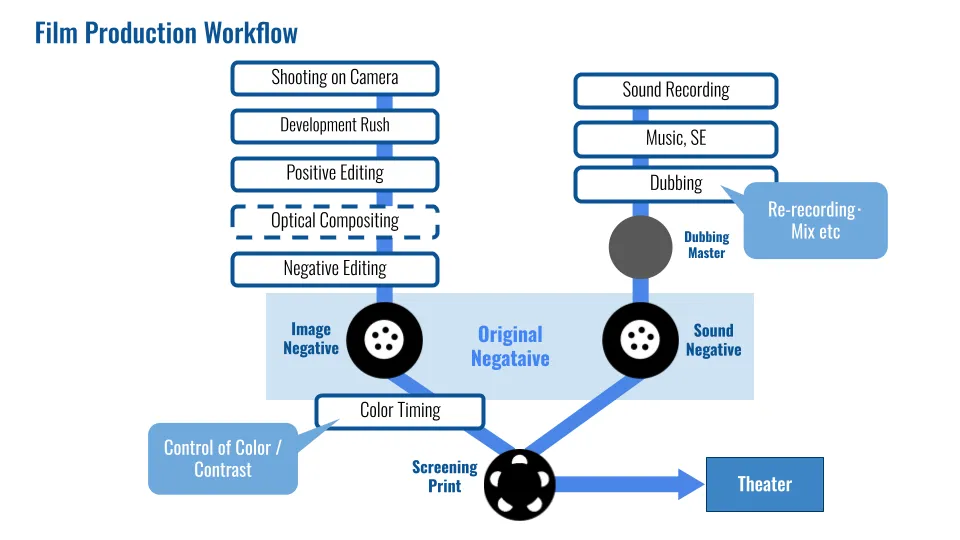

In fact, although we use the term “color” generally, not all color films have the same color. First of all, they have strong characteristics depending on the film manufacturer. In addition, as the industry made improvements in pursuit of better color reproduction and speed, each type (product number) has different characteristics, even from the same film manufacturer. What’s more, the negative film used for shooting and master materials and the positive film used for printing (duplication) and screening each have these characteristics. As a result, we could say the film’s color at the time of its release can ultimately only be reproduced by combining the original negative and positive then used for screening.

When the film is re-used for re-screening, broadcasting, Blu-ray / DVD or streaming, it requires analog-to-digital conversion, in which adjusting the colors to match the output format becomes an indispensable process. If these adjustments are not made correctly, the color of the work viewers see may actually be different from the original.

As a coordinator for this project, I wanted to take the 100th anniversary of Seijun Suzuki’s birth as an opportunity to convey to modern audiences Suzuki’s aesthetics and how he amazed audiences in those days.

This is our second 4K restoration of a Seijun Suzuki film for Nikkatsu, following “Branded to Kill,” as well as our second color film restoration, following “Profound Desires of the Gods.” (Both were restored in 2022 and screened in the Classics selection of the Venice International Film Festival.)

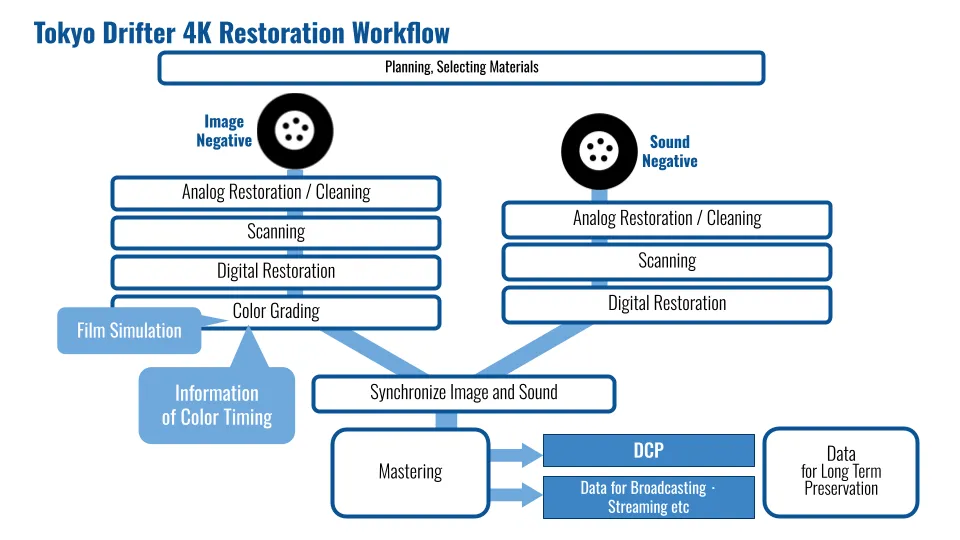

This time, we were looking for a new approach and decided to try color film simulation, which Imagica EMS has been working on for several years. Rather than relying only on the memories of traditional technicians such as cinematographers and supervisors, we proposed to research and study the contemporary colors from 1967, when the film was completed, and reproduce them as authentically as possible in the digital screening. Nikkatsu agreed to take on the challenge with us.

Pursuing the color of “Tokyo Drifter”

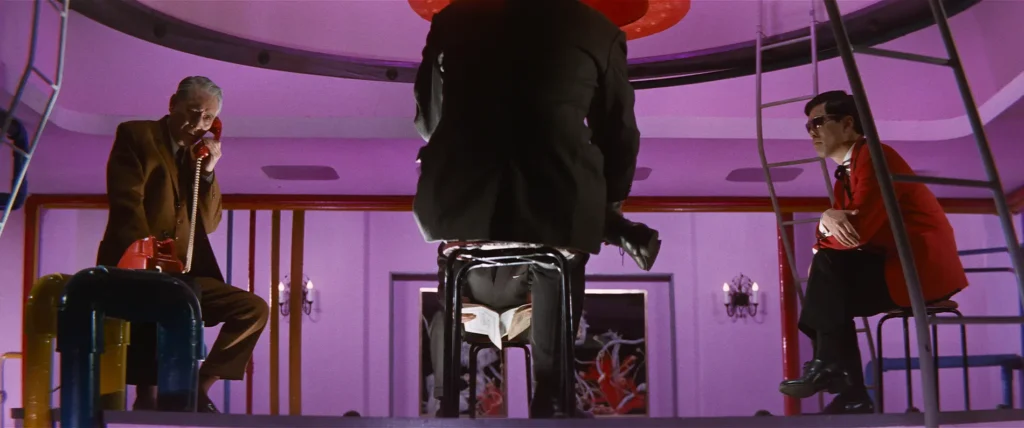

The unique use of color in “Tokyo Drifter” accentuates the production of the entire film, from the trademark light blue suit of “Tetsu the Phoenix” (Tetsuya Watari), “a drifter no matter where he lives,” to the extremely vivid backgrounds and pure white set of the final scene.

“Tokyo Drifter” continues to inspire current directors and cinematographers, including Director Nicolas Winding Refn, who used it as a reference when making “Drive.” What did the colors of such a work look like when the film was originally released? To find out, we started by checking the existing film.

For this restoration project, we received the original 35mm color camera negatives from Nikkatsu’s archive. Although the film had minor scratches, dust, color unevenness, stains, torn frames, curling, acetic acid odor, and other symptoms of physical deterioration, given their long storage period, we could say they were in good condition. We were also able to confirm that the negative film retained much of the color information it had shot.

In general, the next step would be to create a 4K over scanned data from the original negatives, which are the origin of all the duplicated material. However, looking only at the scanned data from the negative film, which is called the original, actually does not reveal the color tones that audiences saw at the time. As mentioned above, theater audiences at the time were only viewing screening prints, positive films duplicated from negatives. A scan of the negatives cannot reflect the color characteristics of the screening print (positive film).

Next, we tried to find vintage prints*1 to use as color samples. If screening prints from that period still existed, we could verify the color by projecting it as well as scientifically analyze them, even if the colors had faded with age. At the time, the film manufacturer had recommended using a combination of positive film “type 5385” with the negative film mainly used for shooting, Eastman Color Negative type 5251 (invented by Eastman Kodak; film produced in 1965 was used for shooting “Tokyo Drifter”). Although we assumed that positive film was used for “Tokyo Drifter,” we needed to confirm what kind of color characteristics it actually had.

However, after a wide-ranging search, we unfortunately learned that no prints from that time remained. “Tokyo Drifter” was a popular film, and prints that have been shown many times wear out. Therefore, they are remade anew each time.

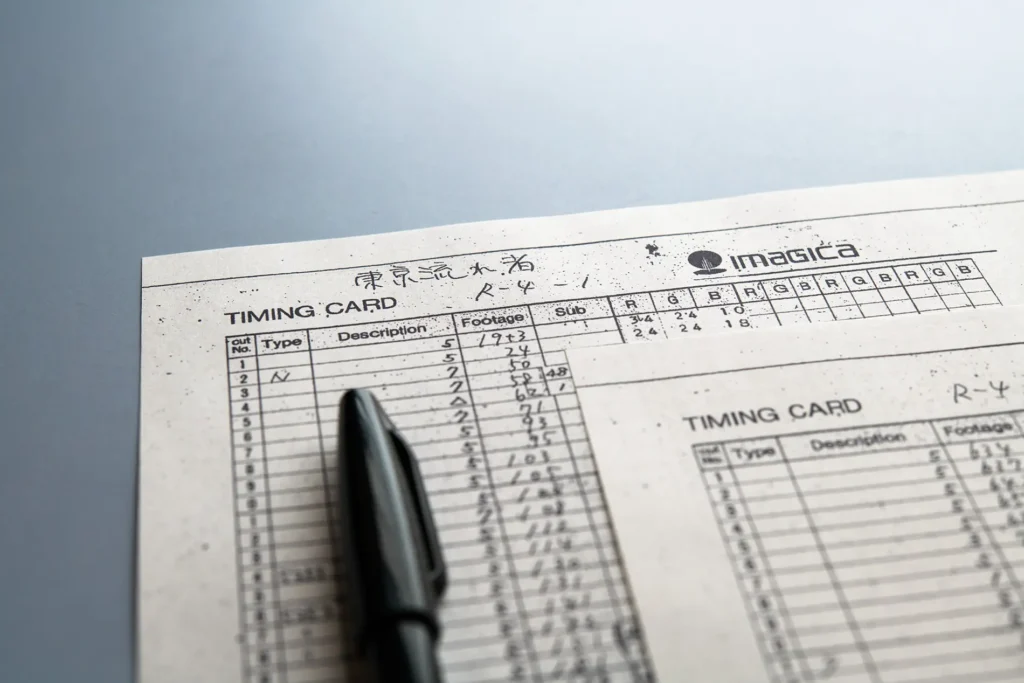

However, we noted from the record of duplicates and labels on the original film cans that we, as the original laboratory, had been in charge of most of the multiple new printing operations, and that the original timing data*2 was inherited, albeit with slight modifications. The timing data had certain minor modifications that we presumed were made to match the prints and film developing machines of the time. This can be seen as actions to reproduce the authentic color design of each original cut as much as possible. Although it is not enough material to grasp the coloring characteristics of the positive film (print) of the time, we were convinced that this would be a great clue as to understand the color direction for each cut. We also projected and checked the oldest existing print (made in 2002) in the screening room.

*1: “Vintage print” refers to print film for screenings that was made using the film stock and developing techniques of the time. Not only the print films of original release, but also the ones that were produced in subsequent periods also have archival value now as previous, irreplaceable materials as well.

*2: Timing data: A record of the numerical values from the process of making prints from original negatives, in which the amount of RGB light is adjusted, and the colors and brightness are directed (corrected) for each cut.

Our approach to achieve “authentic restoration”

The monochrome sequence in the beginning of “Tokyo Drifter” was filmed with a monochrome negative; however, it was duplicated onto a color positive for screenings. The partial-color direction leading into the memorable main title in green, superimposed over evening scenery is a satisfying directorial choice. We were able to confirm it had a finish that makes the slight amber tone visible overall, even in the monochrome parts, through the technical structure of analog duplication.

The existing video master of this part had been digitally converted to black and white by removing the color signal, but through discussions with Nikkatsu, we aimed to restore the look of the original print and decided to adjust the balance to a monochrome tone within the color range, according to the conditions of the time.

In addition, the vivid colors of the costumes and sets were not digitally masked or partially saturated. Rather, we brought out the colors through adjusting the RGB balance in the same way as prints, consistently using the same methods as analog adjustments so that audiences can feel the intensity of the colors.

Discovering valuable information

Although we were able to confirm the production direction, we were still unable to find the color development characteristics of the original positive film. We were about to give up when we discovered a piece of valuable information.

While visiting archives such as the National Diet Library and Oya Soichi Library to research and gather information on “Tokyo Drifter,” I found an article in a 1963 edition of the magazine “Eiga Gijyutsu” (Film Technology) about the characteristics of a certain positive film. The article described the exact positive film that we were looking for, Type 5385, and provided characteristic analysis and objective evaluation of this film at the time of its release.

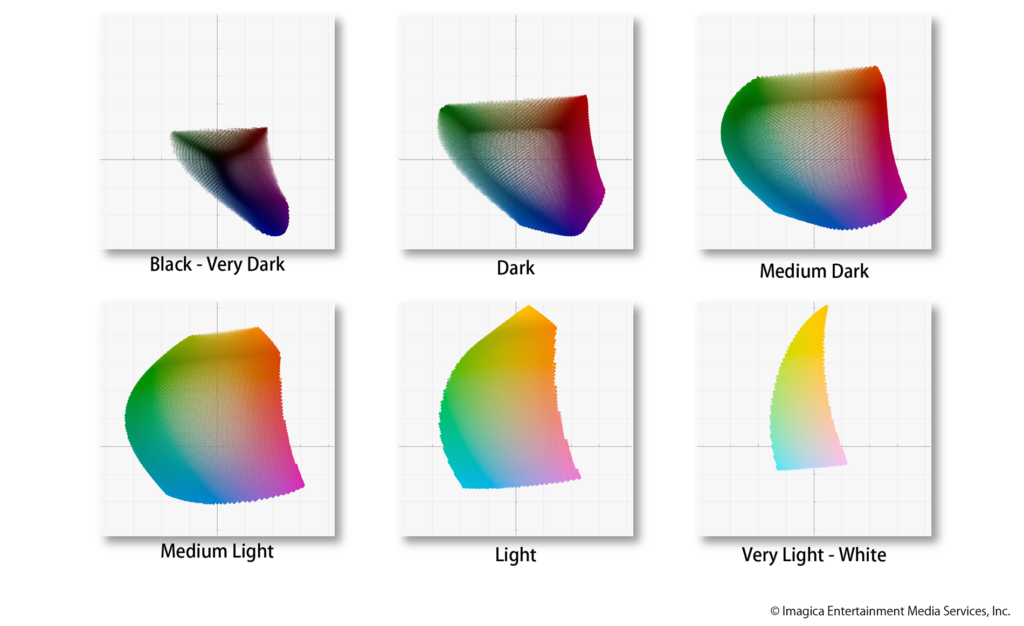

From the magazine’s report, we were able to learn more about positive film Type 5385’s coloring characteristics. Thanks to analysis by our color imaging engineer, we were able to use this information to determine the color range of the film at the time. We could also use these results to limit our color range, even digitally, to those that could be represented by Type 5385. For this project, we developed a plug-in that sets restrictions during digital color grading and issues a warning if it detects colors outside the range that could be represented by printing back then.

Compared to film made in the early days of color in the 1950s, film made in the 1960s has better speed for capturing minute changes in light as well as finer grains and more vivid colors. By combining the negative and positive films, we restored the look of the film to its original theatrical release by incorporating values such as the change in color information at the time of printing. Through conducting simulations under complex conditions, we were able to authentically reproduce the rich color expression of the 1960s, when color films became commonplace, for the digital screenings of today.

To new audiences around the world

When I saw a preview of the finished restored version, I was very moved by the battle scene at the climax, in which, following the work’s flood of colorful scenes up to that point, the characters and their image colors appear momentarily in a white space. I felt we were able to appreciate the film with a fresh perspective, seeing it with new eyes like audiences at the time would have — even though we had seen it many times before — thanks to the 4K restoration’s high resolution, as well as the color reproduction close to that of the originally screened film that we achieved through our approach to this project.

After the preview, the audience talked excitedly about the work, with many referring to the movie’s “color,” which once again made it abundantly clear how important "color" is to this work.

Recreating the characteristics of film in digital media is like tracing the steps of movie history, in which the industry continuously strove to improve over the years. Even if it becomes difficult for those involved in the original production to supervise restoration work going forward, by collecting information on each negative and positive type, we can still follow a scientific approach that doesn’t rely solely on the restoration team’s subjective judgment. I feel that is our mission as a film lab with over 80 years of history.

This project, which focused on authentically restoring the color of “Tokyo Drifter,” was made possible by Nikkatsu finding our proposal interesting, accepting it, and, most importantly, having preserved the film with great care.

Just as “Branded to Kill” was enjoyed by new audiences around the world through its 4K digital restoration, we look forward to “Tokyo Drifter” being rediscovered by many at the Il Cinema Ritrovato film festival and future screenings.

Text by Riko Fujiwara (Archiving and Restoration Coordinator)

With cooperation from Tomohiro Hasegawa (Color Imaging Engineer)

© 1966 Nikkatsu Corporation

“Tokyo Drifter” © Nikkatsu Corporation

Showing at Il Cinema Ritrovato from June 22 (Sat.) to June 30 (Sun.)

Director: Seijun Suzuki

Cinematographer: Shigeyoshi Mine

Starring: Tetsuya Watari, Chieko Matsubara, Tamio Kawachi

https://festival.ilcinemaritrovato.it/en/sezione/ritrovati-e-restaurati-10/

Imagica EMS staff

Archiving and Restoration Coordinators: Riko Fujiwara, Tadaaki Kohnoike

Lab Coordinator: Takahiro Hijikata

Film Repair: Akane Nohara

Scanning: Keisuke Miyabe

Color Grading: Yoshiaki Abe

Sound Restoration: Motohiro Mochizuki

Digital Restoration: Kensuke Nakamura, Yoko Arai

DCP Mastering: Aya Shintani